LOOKING FOR TROUBLE?

STERC'S AUDIT POLICY PAGE

For more information, see EPA's Audit Policy page and FAQs (January 2021).

EPA established an Audit Policy to encourage companies to voluntarily discover, disclose and correct environmental violations. The original Audit Policy was issued in 1995. It was subsequently revised and republished in April 2000. Since 1995, more than 1,150 companies have disclosed potential violations at more than 5,400 facilities. EPA also issued a separate, but related Small Business Compliance Policy in 1996 that was revised in May 2000 to address the special needs of small businesses.

In addition to EPAs self-audit policies, all, but a few states have adopted statutes, policies or rules aimed at encouraging environmental auditing. These include so called privilege and immunity laws, to which EPA is firmly opposed.

The purpose of this feature is to:

- Explain how EPAs Audit Policy and Small Business Compliance Policy work

- Describe the relationship of Federal and state rules

- Give examples of when the policies have worked

- Send you in the right direction for more information

PLEASE NOTE

This feature contains summaries of U.S. EPA policies and state polices and statutes. This information is intended to provide an awareness of these compliance incentives. It is not a comprehensive guide. Before pursuing actions, you should read the full text of applicable items and fully investigate both federal and state policies and laws. Also, you should consider hiring a regulatory specialist who is familiar with both federal and state environmental self-audit policies and laws.

CONTENTS

EPAs Audit Policy

EPAs Small Business Compliance Policy

State Policies and Statutes

Audit Policy in Use

OSHAs Self-Audit Policy

EPAs AUDIT POLICY

EPAs policy on "Incentives for Self-Policing: Discovery, Disclosure, Correction and Prevention of Violations," is commonly referred to as the "Audit Policy." Unlike the Clean Water Act, Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), and the Clean Air Act, the Audit Policy is not a law. Rather, it is a formal statement by EPA explaining the incentives and conditions for self-disclosure of environmental violations. Because the Audit Policy is not a law, EPA can use its discretion, which may or may not work in your favor. However, to date, the policies have been applied on a consistent basis and have proven to benefit some companies.

The Audit Policy applies to settlement of claims for civil penalties for any violations under all Federal environmental statutes that EPA administers. It provides incentives (relief from penalties) when regulated entities discover, disclose, and correct certain types of violations. The Audit Policy does not cover all types of environmental violations and nine conditions exist that limit its applicability. Listed below are the incentives and conditions.

Incentives:

- Elimination of 100% gravity-based penalties (that portion of fine related to violation itself) when all nine conditions (see below) are met. EPA may still levy a fine for any economic benefit that may have been realized as a result of non-compliance. Where violations are discovered by means other than environmental audits or due diligence efforts, but are promptly disclosed and expeditiously corrected, EPA will reduce gravity-based penalties by 75% provided that conditions 2 through 9 are met.

- EPA will generally not recommend criminal prosecution provided that conditions 2 through 9 are met.

Conditions that must be met:

- The violation must have been discovered through either an environmental audit or activities associated with an environmental management system (EMS).

- The violation must be discovered voluntarily, not through monitoring, sampling or auditing that is required by law.

- The violation is disclosed in writing to EPA within 21 days.

- The violation must have been discovered before EPA or other regulatory agency would likely have identified the problem (e.g., does not qualify if EPA is already investigating the facility).

- Must correct the violation within 60 days.

- Must agree to take steps to prevent reoccurrence.

- The same or closely-related violation must not have occurred at the same facility within the past 3 years.

- Not applicable to violations that result in serious harm to the environment.

- Must provide EPA with the information it needs to determine Policy applicability. EPA has not and will not routinely request copies of audit reports to trigger enforcement actions. However, if EPA has independent evidence of a violation, it may seek the information it needs

Companies that wish to take advantage of the Audit Policy should fax or send a written disclosure to the appropriate EPA contacts (see Audit Policy Self-Disclosure & Regional Contacts). Written disclosure must be made within 21 days of the violations discovery.

EPAS SMALL BUSINESS COMPLIANCE POLICY

The Small Business Compliance Policy is similar to the Audit Policy, but it is tailored to small business; it is shorter and simpler and it is easier to qualify for incentives. The Small Business Compliance Policy is available to companies with 100 or fewer employees (across all facilities and operations owned by the small business).

The Small Business Compliance Policy states the EPA will eliminate or reduce the gravity component of civil penalties (that portion of fine related to violation itself) against small businesses when certain conditions are met. EPA may still levy a fine for any economic benefit that may have been realized as a result of non-compliance, although they anticipate that this will rarely occur. Here are the conditions that must be met:

- The small business must discover the violation on its own or through compliance assistance efforts (e.g., state technical assistance provider), but not through an EPA or state compliance inspection, agency information request, or "whistleblower" employee.

- The violation must be discovered voluntarily, not through monitoring, sampling or auditing that is required by law.

- The violation is disclosed in writing to EPA within 21 days.

- Must submit a compliance schedule within 90 days and correct any violations within 180 days (360 days if correcting the violation by means of pollution prevention).

- The same or closely-related violation must not have occurred at the same facility within the past 3 years as evidenced by a warning letter, notice of violation, field citation, or being subject to a citizen suit or enforcement action.

- The company must not have had two or more enforcement actions for environmental violations within the past five years.

- The violation must not have caused serious harm to public health, safety or the environment and must not present an imminent and substantial endangerment.

- The violation must not have involved criminal conduct.

Since 1995 when EPA issued the Audit Policy, 17 states have enacted parallel self-disclosure policies, although several of these policies had specific time periods, which have elapsed (e.g., ID). Most are consistent with EPAs Audit Policy, although they may differ in certain areas, such as the disclosure period (e.g., Connecticut allows 30 days for disclosure). Some states have used the EPA Audit policy as a framework and added program elements. An example is Californias policy, which includes the following provisions:

- Cal/EPA offers a fee-for-service audit/due diligence review that involves the opportunity for facilities which have established an audit/due diligence program to receive certification from Cal/EPA of the adequacy of their program prior to any reporting of a violation discovered through the audit/due diligence process.

- Cal/EPA allows for up to a 90% reduction in gravity-based penalties for companies that choose to invest in pollution prevention programs.

For states that have adopted their own audit policies in federally authorized, approved or delegated programs, EPA will generally defer to state penalty mitigation for self-disclosures as long as the state policy meets minimum requirements for federal delegation.

Twenty-six states have passed self-audit "privilege" and/or "immunity" laws. Most privilege laws protect the disclosure of audit reports. For example, in some states, under specified conditions, an audit report is not admissible as evidence in any civil or criminal proceedings. In most cases immunity state laws, under certain specified conditions, gives a person immunity from fines and in some cases criminal penalties related to non-compliance provided that when the information arises from a self-audit that person makes a voluntary disclosure to the appropriate agency. In exchange, companies may be required to implement pollution prevention and/or an environmental management system.

It is important to closely read your applicable state self-audit privilege and/or immunity laws. Although most have certain common provisions, there are nuances that may affect your decision on disclosure. Some conditions and exceptions associated with state privilege and immunity laws include (a collection from various states):

- Audit must be scheduled for a specific timeframe and announced to the applicable agency prior to being conducted along with the scope of the audit. And in some cases, must be a component of an environmental management system (EMS). (AK)

- The company makes publicly available annual evaluations of their environmental performance. (AZ)

- In exchange for a reduction in civil and/or administrative penalties a company implements pollution prevention or an environmental management system. (AZ)

- Not applicable to data, reports, or other information that must be collected, developed, maintained, or reported, under federal or state law. (AR)

- Audit report is privileged unless a judge determines that information contained in the report represent a clear, present, and impending danger to public health or the environment in areas outside the facility property (CO).

- An environmental audit report is privileged and is not admissible as evidence in any civil or administrative proceeding with certain exceptions, including the material shows evidence of non-compliance with applicable environmental laws, and efforts to achieve compliance were not pursued by the facility as promptly as circumstances permit. (WY)

The EPA has made a clear stand against statutory and regulatory audit privilege and immunity laws that exist in some states. EPA specifically addressed this issue in the Audit Policy:

"The Agency remains firmly opposed to statutory and regulatory audit privileges and immunity. Privilege laws shield evidence of wrongdoing and prevent States from investigating even the most serious environmental violations. Immunity laws prevent States from obtaining penalties that are appropriate to the seriousness of the violation, as they are required to do under Federal law. Audit privilege and immunity laws are unnecessary, undermine law enforcement, impair protection of human health and the environment, and interfere with the publics right to know of potential and existing environmental hazards."

"States are encouraged to experiment with different approaches to assuring compliance as long as such approaches do not jeopardize public health or the environment, or make it profitable not to comply with Federal environmental requirements. The Agency remains opposed to State legislation that does not include these basic protections, and reserves its right to bring independent action against regulated entities for violations of Federal law that threaten human health or the environment, reflect criminal conduct or repeated noncompliance, or allow one company to profit at the expense of its law-abiding competitors."

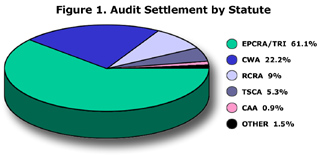

The Audit Policy applies to settlement of claims for civil penalties under all Federal environmental statutes that EPA administers. Figure 1 shows under which statutes it has been applied the most.

The following are real world examples of Audit Policy use.

- A Michigan manufacturer of precision metal parts for airplanes voluntarily discovered and corrected its failure to file Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) reports required under the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA). The Audit Policy made it possible to reduce the original penalty from $60,797 to $5,000. As part of the settlement, the company performed a Supplemental Environmental Project (SEP), which involved the replacement of 2500 lbs. of solvents with a safe water-based process. Another required SEP will eliminate the use of over 7000 lbs. per year of other toxic chemicals.

- Eleven Texas companies that operate facilities in the Maquiladora (U.S. Border) region in Mexico violated the manifest provisions of RCRA, e.g., failure to include an accurate EPA identification number for the hazardous waste, generator, or transporter on the manifest forms. The companies came forward after EPA Region 6 presented the audit policy at a trade association meeting. EPA waived all penalties for all of the companies under the audit policy. Normally, settlements for these types of violations range from $20,000 to $45,000.

- CENEX, Inc., a Montana company, disclosed and corrected its failure to file reports under the Inventory Update Rule (IUR) of the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). The IUR requires manufacturers of chemicals listed on EPAs TSCA Inventory to report current data on production volume, plant site and site-limited status. Under the Audit Policy, EPA mitigated $318,750, which represents 75% of the unadjusted gravity-based penalty, resulting in a total penalty of $106,250.

- General Electric, Inc. voluntarily discovered, disclosed and corrected violations of the Clean Air Act (CAA) at its silicone manufacturing facility in Waterford, New York. The violations resulted from a lack of proper pollution control equipment on two methanol storage tanks. EPA and the Department of Justice agreed to waive the substantial "gravity-based" component of the penalty, which reduced the actual penalty in the case to $60,684, reflecting the amount of economic benefit the company gained from noncompliance.

OSHA published their self-audit policy to encourage companies to detect and correct hazardous conditions at the worksite before accidents occur. The policy (final policy issued July 28, 2000) covers three major issues:

- The policy assures companies that OSHA will not routinely request self-audit reports at the initiation of an inspection, and the Agency will not use self-audit reports as a means of identifying hazards upon which to focus during an inspection. In the past, OSHA authorized its inspectors to demand that companies produce copies of their voluntary safety audits during an OSHA audit. The inspectors could then use the companys voluntary safety inspection as a roadmap to determine the facilitys problem areas.

- In addition, where a voluntary self-audit identifies a hazardous condition, and the employer has corrected the condition prior to the initiation of an inspection (or a related accident, illness, or injury that triggers the OSHA inspection) and has taken appropriate steps to prevent the recurrence of the condition, the Agency will refrain from issuing a citation, even if the condition existed within the six month limitations period (OSHA normally issues citations for conditions that existed as much as six months before an inspection).

- If OSHA identifies a violation during an inspection, but that violation was earlier identified in a voluntary self-audit and the employer is already taking diligent steps to correct the condition, OSHA will use the audit and the corresponding employer action as evidence of "good faith" which may qualify for up to a 25 percent penalty reduction.

To qualify as a voluntary self-audit, the audit must be systematic, objective and documented as part of a planned effort to prevent, identify, and correct workplace safety and health hazards. The audit may be conducted by qualified in-house personnel (competent employees or management officials ) or third party auditors. The audit findings must be recorded and maintained by the employer. Audits already required under a specific standard (such as the Process Safety Management Standard) do not qualify as "voluntary."

Some critics of the OSHA policy feel that it does not provide sufficient protection for most companies because OSHA has chosen to leave the decision to request audit results to the discretion of the inspectors rather than provide absolute "audit privilege". Such critics typically feel that voluntary compliance audits should be completely immune from discovery by OSHA. Labor groups are generally opposed to the OSHA audit policy and argue that it ties the hands of OSHA inspectors in requesting useful information.